Saloni Ambastha

In response to recent trial court proceedings in a case filed by the Delhi Police against members

of a news organisation under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, 1967 (UAPA), this piece

argues that an accused person has a right under Indian law to obtain a copy of the FIR

registered against her under S. 154 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC). This right

is available at all stages of the criminal procedure, including prior to and during investigation.

Access to the FIR under the CrPC

After the Magistrate has taken cognisance of the offence and prior to framing of charges, S. 207(ii) CrPC obliges her to supply a copy of the FIR to the accused. However, the CrPC does not speak to an accused person’s right to access the FIR before this stage, during or even prior to the commencement of investigation. The law on this question has developed through decisions of the High Courts and the Supreme Court, the authoritative judgement being that in Youth Bar Association of India v. Union of India & Ors. [WP (Crl.) No. 68/2016]. Here, the Supreme Court held that the accused is entitled to get a copy of the FIR at an earlier stage than prescribed under S. 207 CrPC, commencing after its registration.

Law Prior to Youth Bar Association

Several High Courts have held that an FIR is a ‘public document’ under S. 74 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 (IEA) and that a certified copy of it must be issued to the accused by public officers having custody of the document (see Calcutta High Court, Karnataka High Court, Gujarat High Court and Allahabad High Court). This is for instances wherein the accused under S. 76 IEA seeks a certified copy of the FIR after its registration, while still being entitled to eventually automatically receive a free copy under S. 207 CrPC. The public officers obligated to supply the certified copy under S. 76 IEA include police officers in charge of a police station as well as the Magistrate to whom the FIR is forwarded within 24 hours of registration, in compliance with S. 157 CrPC.

The Delhi High Court discussed these decisions and the jurisprudence on accused persons’ rights under Article 21 and 22 of the Constitution in Court on its Own Motion through Mr. Ajay Choudhary v. State [WP (Crl.) No. 468/2010]. It held that the accused was entitled to a copy of the FIR at an earlier stage than S. 207 CrPC, commencing after its registration, and laid down detailed directions as to its provision. Other High Courts have since concurred with this position (see Bombay High Court, Odisha High Court, Kerala High Court and Himachal Pradesh High Court).

The Decision in Youth Bar Association

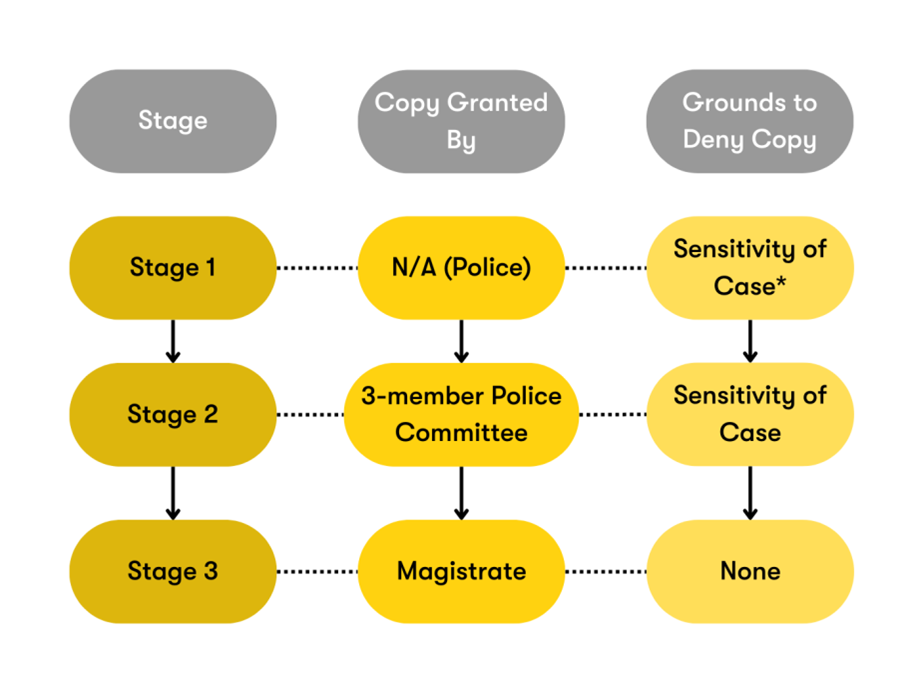

While hearing a writ petition to mandate the uploading of FIRs on police websites across the country within 24 hours of registration, the Supreme Court adopted the Delhi High Court’s directions in Court on its own Motion with minor modifications. Per these directions, an accused ‘who has reasons to suspect that he has been roped in a criminal case and his name may be finding place in an FIR’ can submit an application to the police to receive a paid copy of the FIR, which must then be supplied within 24 hours [paragraph 12(b)]. The accused can also apply for the copy to the court of the Magistrate to whom the FIR has been forwarded, which shall supply it within 48 hours [paragraph 12(c)].

The directions then address the original question of uploading FIRs to the police or government website, ordering that this be done within 24 hours so that the accused can download it and approach the court for any remedies [paragraph 12(d)]. However, the direction in paragraph 12(d) creates an exception to this requirement for FIRs pertaining to offences which are ‘sensitive in nature’, including but not limited to sexual offences, offences under POCSO and terror offences. The decision not to upload an FIR on grounds of sensitivity must be taken by a police officer of the rank Deputy Superintendent or above, or the District Magistrate, and must be communicated to the judicial Magistrate [paragraph 12(e)].

Thereafter, the directions revert to the question of provision of copy to the accused [paragraph 12(h)], stating that if a copy is denied on grounds of ‘sensitivity’ of the case, she can approach the Superintendent or Commissioner of Police, as applicable within each state. The said officer shall constitute a committee of three police officers which will respond to the accused’s request within three days. Where ‘decisions have been taken not to give copies of the FIR’ on grounds of sensitivity, the accused can apply to the Magistrate to whom the FIR has been forwarded, and the copy shall be provided within three days [paragraph 12(j)].

Confusion Regarding Restriction of Access to the FIR by Police on Grounds of Sensitivity

There appears to be confusion within the scheme laid down by Youth Bar Association around whether sensitivity of the case can be used by police as a ground to deny a copy of the FIR to the accused person. This confusion arises because sensitivity is not imagined as an exception to the granting of the FIR copy by the police under paragraph 12(b), which states that police ‘shall’ supply it within 24 hours of the request. Sensitivity is only created as a ground for not uploading it publicly under paragraph 12(d). Yet, paragraph 12(h) seems to transpose sensitivity as a ground even for denial of the FIR copy to the accused by the police. The Court appears to have conflated the obligation of police to supply a copy of the FIR to the accused with their obligation to upload the FIR to their website for public access, despite different interests being served by the two. I argue that while sensitivity is a justifiable ground to restrict public access to the FIR, it is not one to restrict the accused person’s access.

The Court imagines the purpose of uploading FIRs so that ‘the accused or any person connected with the same’, which could include persons not accused of the offence but otherwise mentioned in the FIR, can access it and pursue any legal remedies [paragraph 12(d)]. While not uploading FIRs for public access in ‘sensitive’ cases such as sexual offences and terror cases may be justifiable, the accused even in such cases has a unique interest in accessing the information in the FIR and must be recognised as such within the law. This is necessary to give substance to her constitutional right to legal defence, part of her right to life and liberty under Article 21. For instance, the Kerala High Court noted that the accused cannot exercise her right to apply for anticipatory bail under S. 438 CrPC without a copy of the FIR. In fact, the wide police powers and stringent punishments in special legislations relating to sexual and terror offences make the imperative to protect the accused person’s fundamental rights particularly crucial.

The scheme under which the accused is given a copy of the FIR should be distinct from the considerations behind uploading FIRs online, and sensitivity should not be a ground to deny the accused a copy of the FIR. This distinction is seemingly lost in paragraph 12(h) of Youth Bar Association, which imagines a system where a three-member police committee constituted by the Superintendent/Commission considers the aggrieved accused’s request and communicates its decision to her within three days.

However, the confusion in paragraph 12(h) of whether sensitivity is a ground for police to deny the accused a copy of the FIR does not affect her right to obtain a copy of the FIR from the Court. The procedure of deliberation by a police committee only causes an unnecessary delay. This is because under paragraph 12(j), an accused person aggrieved by the police committee’s decision can apply for a copy to the Magistrate to whom the FIR has been forwarded, who shall provide it ‘in quite promptitude’ within three days. Similar language mandating supply of the FIR copy by the Magistrate is used in paragraph 12(c), which precedes the ‘sensitivity’ exception. Notably, paragraphs 12(b) and 12(c) also do not require the accused to exhaust an application to the police before approaching the Magistrate. Therefore, the position of law is clear – the accused has a legal right to a copy of the FIR.

An Arrestee’s Right to a Copy of the FIR and Written Grounds of Arrest

The directions in Youth Bar Association pertain to a person who apprehends that he has been accused of an offence in an FIR. This naturally includes an arrested person, who by virtue of being arrested becomes aware of having been accused of an offence. The Bombay High Court has also specifically held that the copy of the FIR must be provided to the accused before or at the time of arrest.

An arrested person also has the right under Article 22(1) of the Constitution, incorporated under S. 50(1), 55 and 75 CrPC, to be informed ‘as soon as may be’ of the grounds for arrest (see here and here). These are distinct from the FIR, which contains information regarding the offence. While an FIR may name the accused or describe her role in the commission of the offence, the grounds for arrest must specifically justify why the liberty of the accused needs to be curtailed in the context of the case. S. 41 CrPC lays down when a police officer may arrest a person without a warrant, while Chapter VI Part B CrPC details the procedure of arrests through warrant.

The question of whether the grounds for arrest must be communicated in oral or written form was recently addressed by the Supreme Court. The Court upheld the right of arrested persons to be given written grounds of arrest, as part of their constitutional right to be ‘informed’ of them under Article 22(1). While the judgement dealt with a case under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (PMLA), the reasoning given by the court is applicable to all arrested persons.

Conclusion

The confusion in the Court’s directions in Youth Bar Association has allowed the police in different states to subjectively interpret their obligation to give the accused a copy of the FIR. For instance, the Delhi Police and Odisha Police circulars in interpreting ‘sensitivity’ of cases allow officers to deny the copy in any case where ‘desperate criminals’ are involved, where there is danger of intimidation of witnesses, where one accused has been arrested but others are at large, or where the Deputy Commissioner otherwise considers the matter sensitive.

Misinterpretation of the dictum in Youth Bar Association also crops up in individual cases, as played out in the 5th October 2023 hearing in the UAPA case and before it in NIA cases or offences under the Official Secrets Act. While in these cases Magistrates elected to provide a copy of the FIR to the accused, no accused person should be at the mercy of executive and judicial ‘discretion’ in accessing the FIR, in light of the authoritative judgement in Youth Bar Association.

Saloni Ambastha is an Associate (Forensics) at Project 39A, National Law University Delhi.